Overview of Bulgarian Economy

Overview (2013)

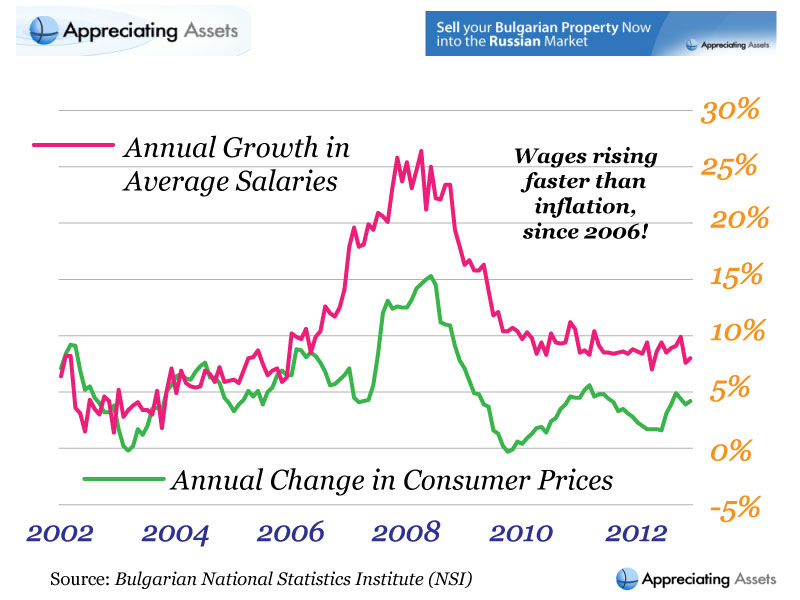

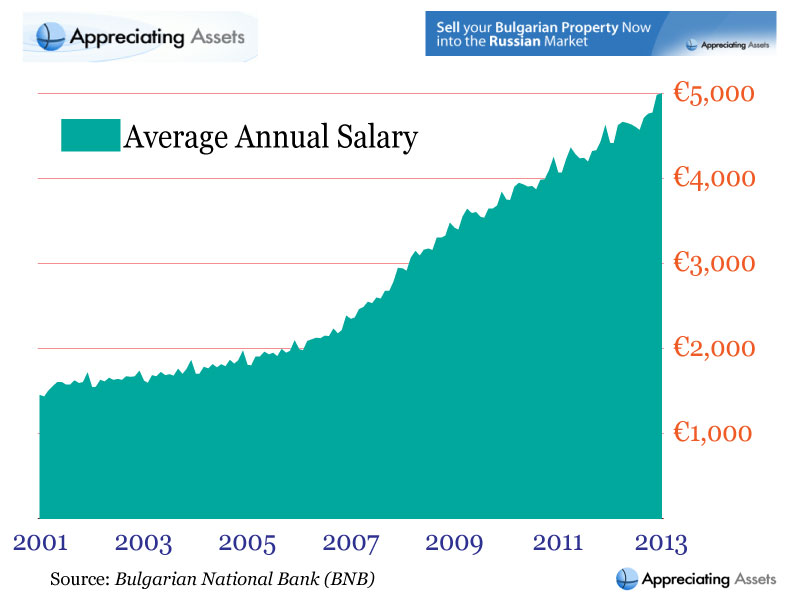

When we think of the emerging European economies of the East, the former communist bloc countries, we immediately view them as high growth and rapidly developing nations, particularly so as we correctly see them coming from a very low base (low that is from a developed world country perspective), however this perception is often too simplistic. Indeed, just examining the recent economic stats for Bulgaria, for instance a jobless rate of 12%, growth stagnant at a mere 1% (so far in terms of output for 2012), whilst inflation has picked up significantly during the latter part of 2012 and by January this year was rising at almost four-and-a-half percent annual clip. On the positive side, total Bulgarian government debt is very low by international standards, and although average wages and salaries have been rising at nearly twice the rate of annual inflation, but at just under €5,000 they are still quite modest when compared to the rest of the European Union.

Annual average incomes in Bulgaria have been growing at twice the rate of inflation since the summer of 2006, yet this may be viewed as a double-edged sword, firstly; from an international property investors perspective it allows domestic residents the ability to borrow more for the purchase of a home, on the other hand however; it reduces the competitiveness of the labour market from a direct foreign business investment viewpoint. Indeed, Bulgaria has had a long and unforgiving history with problematic inflation, so much so that they resorted to pegging their currency – the Lev – to the German Deutschemark back in 1997, which is why today, in the post-Euro world, that the Bulgarian Lev (or BGN) is fixed at 1.95583 equals €1.

To many foreign investors, this fact, coupled with EU membership was the underlying rationale for investing in this country in the first place. Notwithstanding this apparent perennial rise in the general price level as well as increases in average wages and salaries, domestic property prices do not always benefit from such volatile and persistently high rates of inflation. Contrary to popular belief, home values do not always keep pace with ‘high’ annual rates of inflation, especially when there remains so much uncertainty regarding this annual rate of inflation which has obviously fed into workers wage expectations. It is nigh on impossible for any country to maintain double-digit wage inflation.

Growth Profile

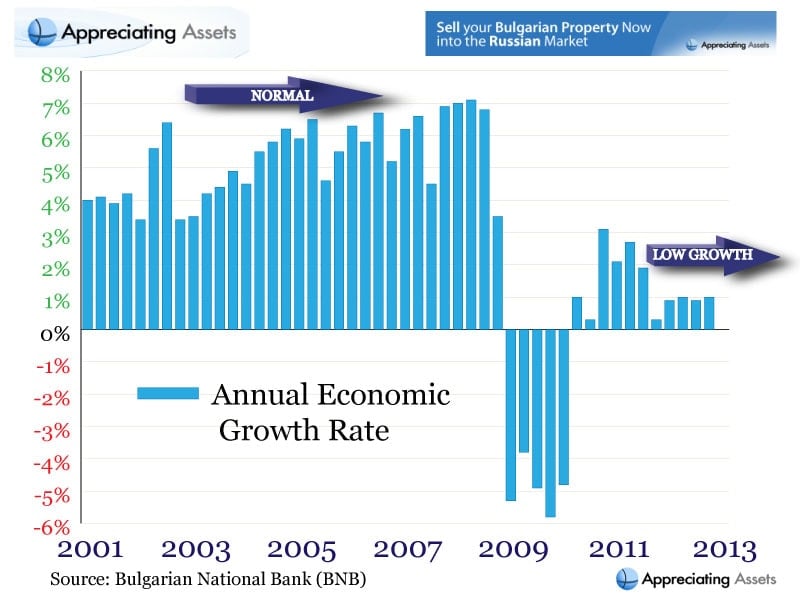

Developing nations like Bulgaria need comparatively high Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rates, typically above 5% per annum (in ‘real’ or inflation-adjusted ‘output’ terms), both to raise income and living standards, but also to allow the country to bring their infrastructure development up to OECD (developed world) standards. It is not fair to compare developing nations with fully developed economies using the standard metric of annual economic (or GDP) growth, because what constitutes a technical recession in for example the UK or Ireland (zero or negligible growth) would equate to a severe recession from a Developing Country (DC) perspective. Likewise, real growth of +2% to 3% in western economies is analogous to +5% to 7% in developing nations. Consequently, when one views the historical growth chart below for Bulgaria over the last decade, one has to bear this proportionality factor in mind.

It is evident from the figures above that Bulgarian real output growth averaged around 5% a year during the first half of the last decade – what could only be described as a period of ‘normal’ growth for a developing economy. However, as the figures also shows clearly, Bulgaria was not immune to the global slowdown and that even this pace of sluggish growth since 2011 should really be seen as still recessionary from a developing nation perspective. Furthermore, the growth outlook for this year, 2013, is not much better with the IMF now forecasting a very disappointing +1.5% expansion in GDP. Unfortunately, the IMF have been wrong about the anticipated bounce back in output for most countries when they made similar projections this time last year. The economic landscape could best be described as more of the same, namely; very weak.

There is a simple rule of thumb when looking at any country in the world, that in order to bring back down the unemployment rate by say 1% per year, the economy has to grow by at least 3% to 4% (depending on the size of the economy and whether or not it is export-oriented, and the proportion that the State makes up of the overall pie in terms of government spending). In a nutshell, what this 3:1 or 4:1 ratio tells us, is that Bulgaria is not growing anywhere at or near what they need to be in order to make any significant impact on the huge numbers now unemployed. This apparent slack in the economy will therefore continue to act as a drag on any future growth prospects. This is what economists’ like to call a negative feedback loop, or what most people would refer to as stalemate.

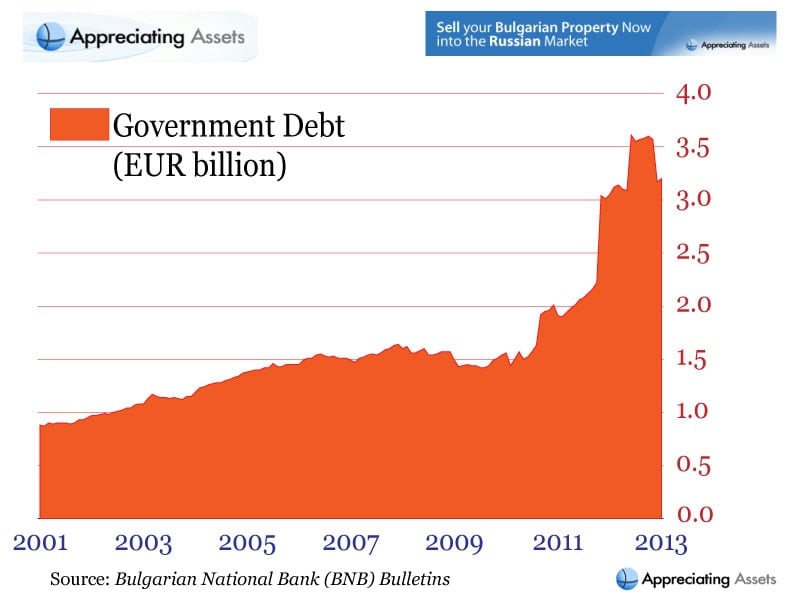

Bulgarian National Debt - Burden Is Low

When we speak about government debt or the national debt, there are two sources: domestic and external, but in reality we are talking about the total outstanding government plus government guaranteed debt, which by the way in Bulgaria is below the EU-average at less than 25% of the size of the economy. As our next graphic shows; in absolute money terms the Republic of Bulgaria has a total debt outstanding of just €3.5 billion, which for a country with a population of nearly 7.5 million persons is actually quite small when compared to say the Irish or British national debt (per capita). The low debt position of the country is one of the few economic positives at present.

Rising Unemployment

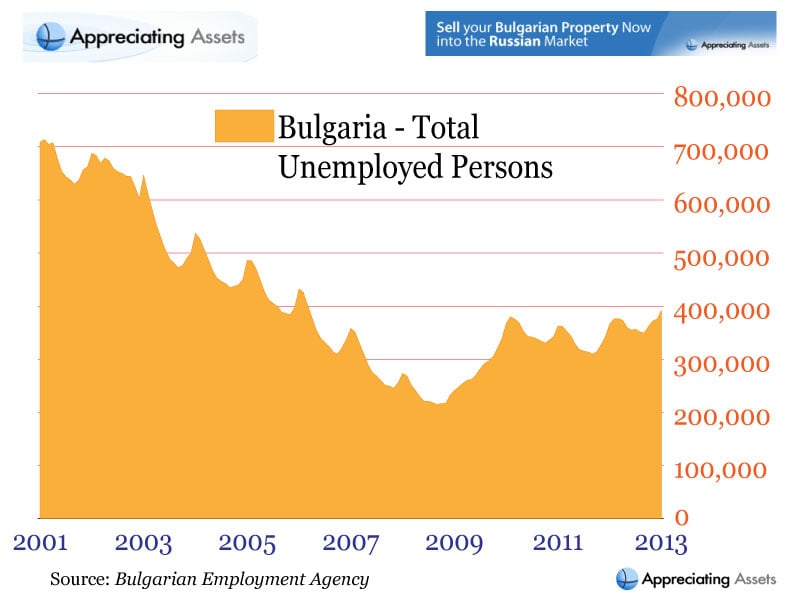

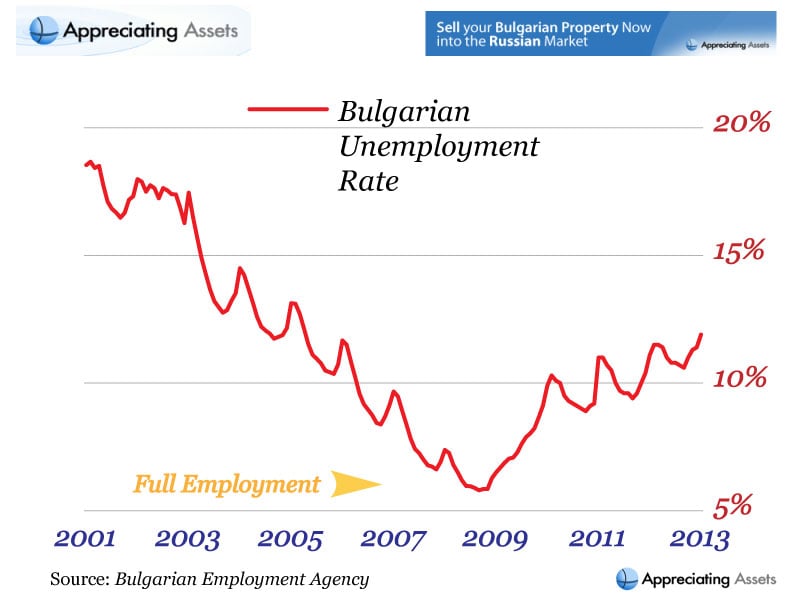

The employment picture in Bulgaria at present is quite similar to that of the Irish Republic, in a word; very bleak. As our next graphic illustrates very well, Bulgaria made big strides in reducing joblessness during the early part of the twenty-first century, reducing the dole queues from 700,000 people, down to approximately a quarter of a million men and women out of work by late-2007, with further improvements when only 215,000 persons were claiming unemployment benefits by September 2008. Now that date will stick in the minds of most people as the same month that the Global Banking Crisis hit its peak (remember the collapse of Lehman Brothers in the US and the Irish blanket bank guarantee). Bulgaria was very close to full employment back then.

Looking at the numbers of jobless in the usual way – expressed as a percentage of the total labour force – the unemployment rate was below 6% back in September 2008, but has subsequently doubled to almost 12% by January 2003. Another interesting feature of the jobless rate in Bulgaria as evidenced by the next chart, is the seasonality pattern. Bulgarian unemployment typically rises in the late-winter or early-spring, then usually dips during the summer months.

Those familiar with the Bulgarian property market, especially investors in the Black Sea area will not be surprised by this trend, however they may be dismayed at just how bad the jobs market is in Bulgaria at present, particularly in the knowledge that it would take 7-8 years of decent economic growth (4%-plus level) to return the labour market back to the situation prior to the banking crisis.

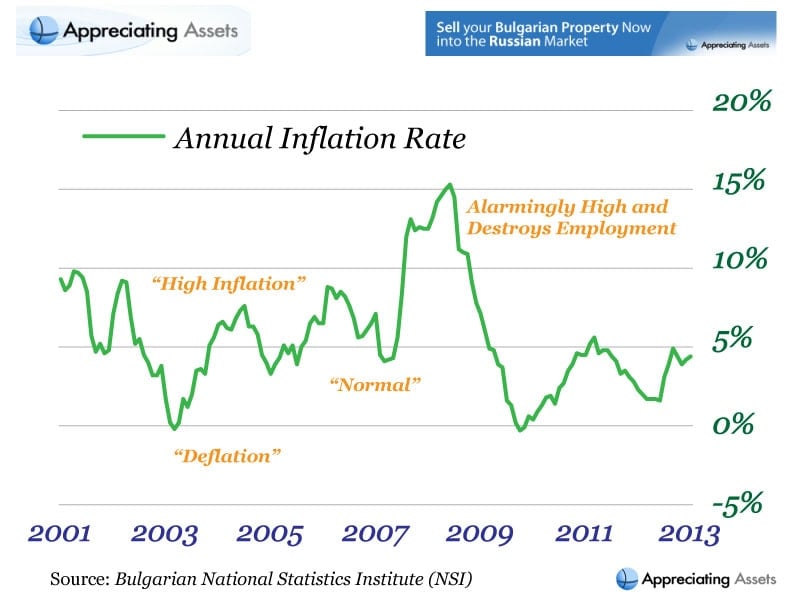

Consumer Price Inflation: "A Roller-Coaster Ride"

It is no secret that Bulgaria has always had a problem with high inflation. Not just persistent inflation but significant volatility in the absolute level of inflation too. For any modern economy, it is really important to keep a lid on the general price level. Inflation has often been described as the “mugger in your wallet” and is in many respects like a disease, like ‘cancer’ – once you have an inflationary problem, it grows and feeds on itself and becomes the dominant factor that consumes the attention of both politicians and consumers (workers). There is no such thing as good inflation. Businesses and employers are always reluctant to hire new workers when there are ever increasing wage demands from their current workforce, even when the pace of sales is brisk. Business owners like everyone else in society need some degree of certainty before they make major investment decisions. We all know that another word for uncertainty is ‘risk’, thus it is so with persistently high or volatile inflation. It took a major recession in 2009 to bring Bulgarian inflation back down to earth.

Today, inflation in Bulgaria remains high by international standards, at 4.4% in January 2013. A lot of property investors may be under the illusion that a little bit of inflation is good for ‘real’ assets such as land or property, and to a degree this is possibly true over extended periods of time, for instance 30 or 40 year horizons, but it does not mean that asset prices follow the trend in consumer prices. The proof of the pudding is in the eating as they say, and despite a slight deflationary period in late-2009, inflation has subsequently resumed in virtually all countries in the world, yet property crashes have continued unabated in many markets, Bulgaria being no exception.

Wages & Salaries Rising, But Are Still Low

Ask any personnel manager or HR Director of any organisation that you know, about workers attitudes towards the ‘cost of living’, and they will invariably tell you that employees see any rise in inflation as a God-given right to an immediate pay rise. Pay scales in Bulgaria have been increasing at a substantial rate, especially when compared to increases in the general price (inflation) level.

Notwithstanding this, when compared to the rest of the EU, or to countries like the UK and Ireland, absolute annual wages and salaries in Bulgaria appear minuscule (see above chart), a factor often overlooked by international investors who tend to use their own frame of reference (influenced by their own domestic economy) when seeking to invest abroad – they forget the most important question, which is; “what can the local people afford?”.

According to the Bulgarian National Statistics Institute (NSI), the average monthly Bulgarian salary at the end of 2012 was BGN 812 or EUR 415 that equates to an average yearly wage of just under five thousand euros (see table below for a further breakdown by industry, public versus private sector, as well as some historical perspective). In the interests of brevity and to spare the reader boredom, we have truncated the table to show a decade ago, plus the most recent figures available. This table illustrates average monthly wages (plus an annual average column)

|

Period |

Annual Average |

Monthly Bulgarian |

Public Sector |

Private Sector |

Agriculture & Fisheries |

Industrial Sector |

Services Sector |

| Jan-01 | €1,448 | €120.66 | €131.40 | €110.95 | €91.52 | €126.29 | €118.62 |

| Feb-01 | €1,430 | €119.13 | €129.87 | €109.42 | €88.96 | €124.24 | €117.60 |

| Mar-01 | €1,503 | €125.27 | €139.07 | €113.00 | €93.57 | €132.94 | €122.71 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Feb-06 | €1,976 | €164.64 | €196.85 | €149.81 | €119.13 | €163.10 | €168.22 |

| Mar-06 | €2,086 | €173.84 | €210.14 | €156.97 | €123.73 | €173.33 | €176.91 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | .... | .... | ... | ... |

| Oct-08 | €3,301 | €275.08 | €352.28 | €247.98 | €210.14 | €262.29 | €285.30 |

| Nov-08 | €3,325 | €277.12 | €351.77 | €250.53 | €199.92 | €267.92 | €285.81 |

| Dec-08 | €3,473 | €289.39 | €377.84 | €257.69 | €205.54 | €272.52 | €303.20 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| May-12 | €4,651 | €387.56 | €411.59 | €378.36 | €275.08 | €358.93 | €406.99 |

| Jun-12 | €4,632 | €386.03 | €400.85 | €380.91 | €312.40 | €363.02 | €400.85 |

| Jul-12 | €4,602 | €383.47 | €398.30 | €378.36 | €313.42 | €358.42 | €399.32 |

| Aug-12 | €4,565 | €380.40 | €397.79 | €373.75 | €298.59 | €355.86 | €396.25 |

| Sep-12 | €4,712 | €392.67 | €417.21 | €382.96 | €373.24 | €369.66 | €404.94 |

| Oct-12 | €4,761 | €396.76 | €434.09 | €382.45 | €306.78 | €360.46 | €419.26 |

| Nov-12 | €4,773 | €397.79 | €408.52 | €393.69 | €304.22 | €369.66 | €416.70 |

| Dec-12 | €4,982 | €415.17 | €442.78 | €404.43 | €360.97 | €378.87 | €436.13 |

Clearly, your average Bulgarian national is rather limited in terms of the amount of money that they can borrow to fund the purchase of a home or indeed a holiday home. Obviously this is an important consideration for any investor considering purchasing or selling a property in Sofia or the Black Sea coastal area.

Domestic Mortgage (Home Loan) Rates

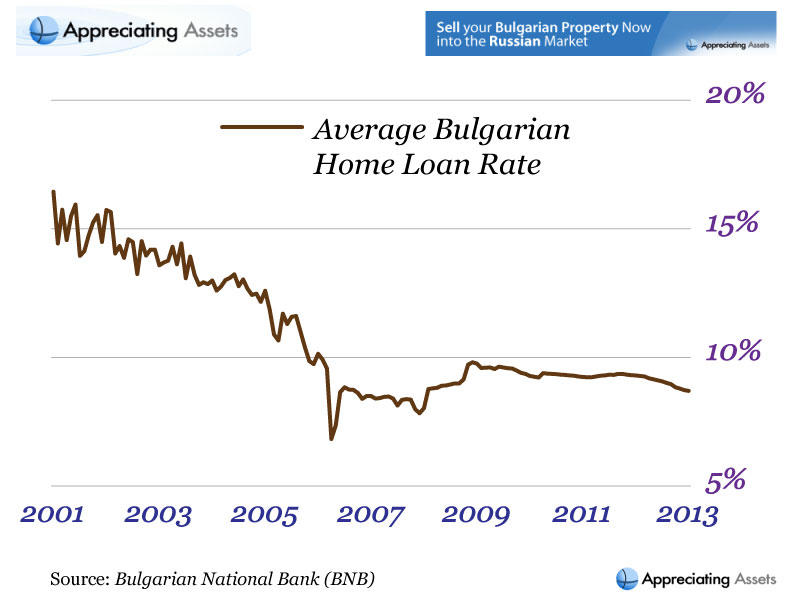

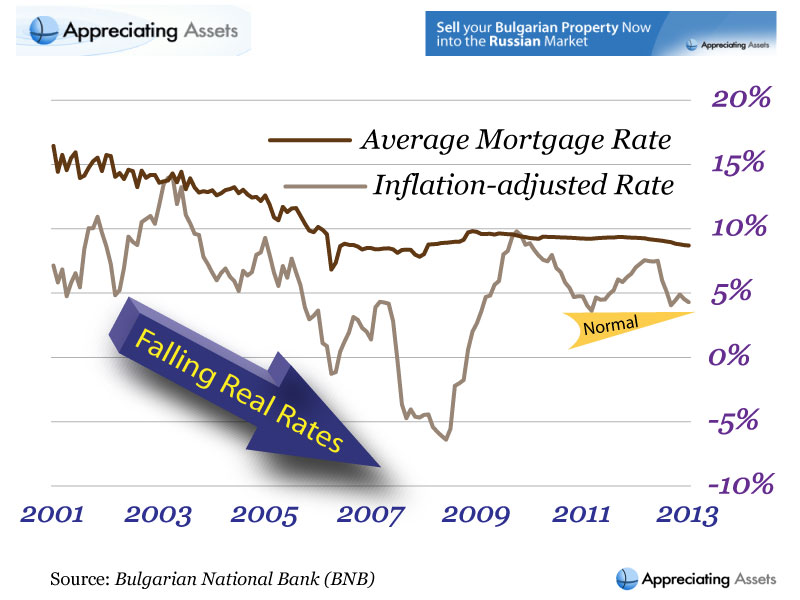

The Bulgarian National Bank (BNB) publishes selected interest rates applicable to citizens for loans greater than 5 years in duration for the express purposes of purchasing a home. Firstly, we should caveat that the corresponding figures for EUR-denominated loans would historically have been a couple of percent lower, obviously depending on whether a particular borrower had an income in euros or a euro-denominated bank/savings account. Until quite recently, not many Bulgarians had a foreign source of income or a business/job that paid them in a non-domestic currency. Therefore, the long-term mortgage rate that applied to households was the one depicted in our next graphic:

Compared to other-EU countries, either inside the Eurozone or outside (like Britain), these average mortgage rates shown above, may seem rather high. Then again, we need to refer back to the extremely high aforementioned inflation rates that go a long way towards explaining these numbers.

Our second chart highlights the average mortgage rate alongside the ‘real’ rate (minus inflation) and it becomes patently clear that it was this declining effective rate that drove the property boom from 2003 to 2008 as the inflation-adjusted mortgage rate fell by almost 20%! (+15% to -5% in real money terms).

What should still be borne in mind is that even in today’s market, Bulgarian nationals, still have to pay more than 8% for home-loans in comparable euro terms. This is more than double the Irish average mortgage rate of about 3.2% based on Central Bank of Ireland monthly statistics bulletins. So even though Bulgarian property prices have fallen by two-fifths or more, coupled with a near doubling of the average wage since 2007, Bulgarians still have to pay a lot more for their credit than the British or Irish do (primarily because of their pernicious inflation rate which has not benefitted the domestic property market in recent years).

Negative real interest rates are not a new phenomenon and indeed, are quite commonplace nowadays, especially as governments are deliberately keeping longer term interest rates down using Quantitative Easing (QE) – by printing new money ‘electronically’ at their respective central banks (using just a computer and a keyboard and then crediting this new money to bank accounts of the major commercial banks in return for buying back government debt or bonds off them). Whereas negative real interest rates can support or buoy a market during boom times (or some might say “fan the flames of the property fire”), when times are tough, like now, they merely cushion the fall somewhat. In other words, it could be a lot worse if rates were allowed to revert back to long-term average levels.

Summary Outlook

The only message that anyone can credibly claim right now is that economically things may not get any worse, but they’re not going to get that much better anytime soon. In brief, the outlook is for more of the same in the short-term (that is up to 1-year), but in the medium term (3-5 years) we ought to see a gradual improvement in growth, and then some time later this should feedback into better prospects for the labour market. This adjustment process in recovery is always a gradual one, jobs may be lost quickly, but it does take more time for joblessness to recede. The construction sector is a good example of how potential recovery may be stymied by the past excesses in new building, as the supply overhang (especially when one accounts for the large quantity of property resale’s by investors who bought off-plan with a view to flipping for a profit) remains quite large.